For the next few weeks, we are featuring some of our favorite blogs from years past. This entry was first published by In Care of Dad on February 17, 2011.

by Ann Meyers Piccirillo

“I will never leave you — no matter what happens I will always be with you.”

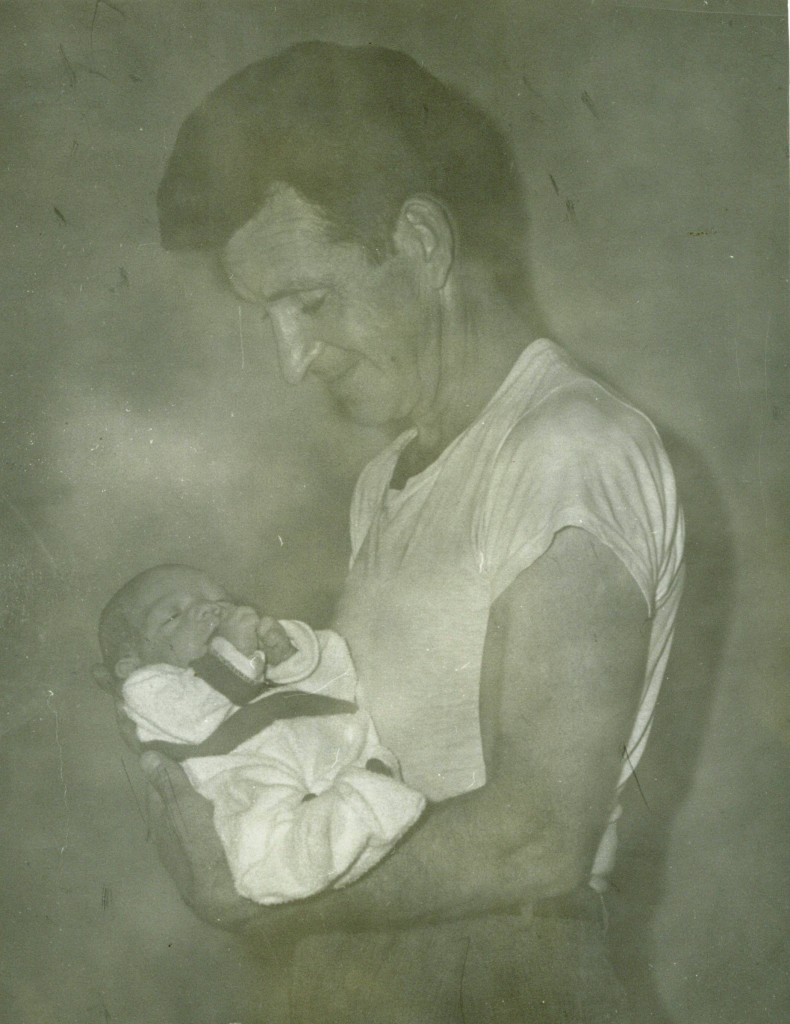

Unbeknownst to both of us at the time, those would be the last words my father would ever say to me. That one sentence would carry me into my fatherless future, like a road map to guide me on the sometimes perilous, sometimes heartbreaking, always blessed journey of my life.

I was only a freshman in college when one day I walked into my family’s living room and found my father on the floor, gripping a red handkerchief to his mouth, coughing violently, his body wracked with spasms as he gasped for breath. He couldn’t respond to my panicked cries of “Daddy, are you all right?” I hurriedly called for the paramedics, and it wasn’t until my father’s suddenly frail-looking body was strapped to a stretcher that I realized the handkerchief he’d been clutching to his lips had been dyed red with the blood he tore from his lungs with every savage cough.

My father was expected to die that day, but his heart would not comply. As he lay in the ICU late that evening, he took my hand and held it tightly in his own warm palm.

“I love you,” he said softly, his breathing still labored but his eyes holding me firm. It was the first time I remembered hearing those words come out of his mouth. Not because his love was ever in question — no, just because words like that didn’t come easily to the reticent men of his generation.

“I love you too, Daddy,” I told him, because I did. So very much, in fact, that I didn’t think I could leave him there all alone in the sterile glare of the ICU’s cold fluorescent lights. But the nurses told me I had to let him rest — one lung was not functioning at all, the other was severely scarred, and the heart murmur he’d been born with had done its final damage. Operating was no longer an option, which made a transplant also out of the question. I backed out of his glass-enclosed room, moving slowly, my eyes refusing to leave his. I was afraid to look away because I was sure I would never see him alive again.

But he made it through the night, and actually survived the following 1,092 days, though with more time spent in ambulances and hospitals than at home. I was forced by the circumstance of my father’s illness to assume the role of medical decision-maker. I didn’t particularly want the role, nor did my father want to cast me that way, but, well, there we were. He didn’t know how to relinquish the fight for his life, and even though people kept telling me I had to let him go, I didn’t know how to do it either. I struggled everyday with this question: How do you say, without regret, without remorse, that it’s okay to let vanish the life that sparked your own?

During the worst moments of my father’s ordeal, I sometimes envied those children whose fathers were lost to heart attacks, car accidents, strokes, anything that happened quickly and carried a pain that a family could easily surmount. Or so I thought at the time. I know now that the pain of death is just as devastating no matter how it comes about, and is never surmounted, easily or otherwise. It’s dulled, but never erased. And I also now recognize that a sudden death would have deprived me of the long days spent talking with my father, filling those antiseptic hospital rooms with peals of laughter and the vivid colors of his recollections.

During those talks I learned that my father lived a fascinating and enviable life. Before marrying my mother he traveled the world as a professional caddy; he fought in the Philippines and Japan during WWII and spoke of the horrors of the A-bomb; he was a merchant marine whose stories brought to life the beauty of Cuba before Castro; he owned a pool hall in Fort Lee that the all-mighty Monsignor of Madonna Church made it his mission to close down; he owned a dry cleaning store on Main Street that ran legendary high-stakes poker games after-hours; he organized countless unions and fought tirelessly for what he believed was right. I learned all about the man behind my father. I listened without comment. For even then, at the age of 20, I knew that his stories would infuse me with the courage to live my life as boldly as he had.

Once, while on a rare visit home from the hospital, he became too weak to walk and I carried him to the bathroom so that he could stand to pee like a man, because at that stage of his life (or, more aptly, at that stage of his slow death), standing to pee was all he had left of his dignity, and I was determined to preserve it.

He was exhausted, out of breath, and in a great deal of pain, but he put all that aside to smile at me. “Thanks for the ride,” he said, “but next time I think I’ll take the bus.”

It was more important for him to make me laugh than to succumb to the failings of his own body. He redeemed that moment with laughter because he refused to have me live with the memory of his weakness, and instead imparted to me his unquenchable strength.

Another time, while lying in his hospital bed, sustained only by a thin plastic tube of oxygen, he told me, “I can’t make this world a kinder place for you. But I showed you commitment and I gave you strength, and if you know nothing else, know that whatever happens, life can never break you.” These words were spoken many years ago but I still hear them like it was yesterday.

This week my father’s voice will have been gone from this world for a quarter of a century. And yet, as one year follows another, I still find myself looking for him, and in the moments when I need him most, I follow his memory to the places that he loved — the cliffs of the Jersey Palisades or the banks of the Hudson River, where every rustle of leaves and breath of salty air carries a trace of his voice.

Every Father’s Day I visit the cemetery where he rests and I pour a snifter of Irish whiskey upon his grave, to honor the man who gave me life and good humor and, most of all, the gift for knowing that no moment is ever truly ordinary. I toast him to remind myself I have a father who is with me every day. After all, I came into this world as his daughter — that relationship doesn’t stop with the last beat of his heart. Nor will it stop with the last beat of mine.

So join me in the tradition of toasting my dear old Irish dad; and here’s to yours, whether his spirit dwells beside you or inside you.

“May the roads rise to meet you, may the wind be always at your back, may the sun shine warm upon your face, the rain fall soft upon your fields, and until we meet again may there be a generous bartender waiting to serve all us heathens in heaven.”

Ann lives in Leonia, NJ and you should check out her column called — Mom to Mom: Motherhood, Madness & Merlot.

That is such an incredible way to honor your Father, the story and the Irish Whiskey. It touched my heart so much that I had to read a few passages a second or third time because my tears of; sadness, joy, pride, and love, that you must have felt filled my heart. Thank you so much for sharing this.

Thank you for giving me courage tonight. Like you, I had a remarkable father. Like you, my father is now gone physically (Dec 9, 2013). And like you, God and life gave me a few years to release him slowly, every visit treasured. But my grief is new, and the longing for him is still raw, springing up at strange moments in my day. Thank you for your words.