by Karen Keller Capuciati

“I want her to tell me what she’s thinking and feeling, what she dreams about that makes her yell at night.”

But for Kari, who posted this concern on the In Care of Dad Facebook page, it’s not possible for her mom to tell her. She has dementia and has lost the ability to form words. “I can’t understand Mom any more,” Kari wrote. “I haven’t been able to in over a year.”

Her mom understands what others say to her — she can answer “yes” and “no” — but Kari feels that her mother has more she wants to say and it’s breaking her heart.

So I reached out to a group of geriatric-care professionals, with whom I meet once a month, to get some suggestions for Kari. Without knowing all the specifics of Kari’s situation, the group had some creative ideas for building a meaningful connection with a loved one when verbal communication has become severely limited.

Mary Underwood, Vice President of Memory Care at Maplewood Senior Living in Fairfield County, CT, believes that all her mom may need is a genuine connection. “Trying to have someone answer questions that they are not able to can be frustrating, not only for the caregiver but also for the person with the disease,” Mary said. “It is important to provide reassurance that they are okay. It can also be helpful to acknowledge the frustration that the person is experiencing. To say, ‘I know it must be hard to not be able to get the words out’ or ‘Even though you can’t tell me what you’re feeling, I want you to know that I am here to make sure you’re okay’ are comforting statements for your loved one. Understanding and connecting with the emotion they are experiencing is often more important than the fact of what is happening.”

Kathryn Freda, a gerontologist and eldercare manager, has had positive experience with elders using art to express themselves. “If it seems like an activity that they might be willing to participate in, I would ask my loved one to draw with pastels or larger crayons, or paint with a wide brush or fingerpaints, or mold clay into shapes. Art transcends normal thought,” Kathryn explained, “and I have often seen clients convey emotion through form and color.”

Joan Blumenfeld, a geriatric care manager in Fairfield County, CT, took a different approach. She thought acceptance of her mother’s current disabilities was a healthy and helpful place for Kari to start. “Kari’s wish for her mother to communicate more is understandable, but unrealistic,” Joan stated. “Changing her expectations for her mother is a first step — perhaps an Alzheimer’s support group would be useful to her.

“Also, I would recommend comforting her when she seems to be afraid, like you would with a small child who is frightened. If she is yelling at night, ask yourself: does she need to go to the bathroom? Is she too hot or too cold? Does she have a nightlight? What might be troubling her?”

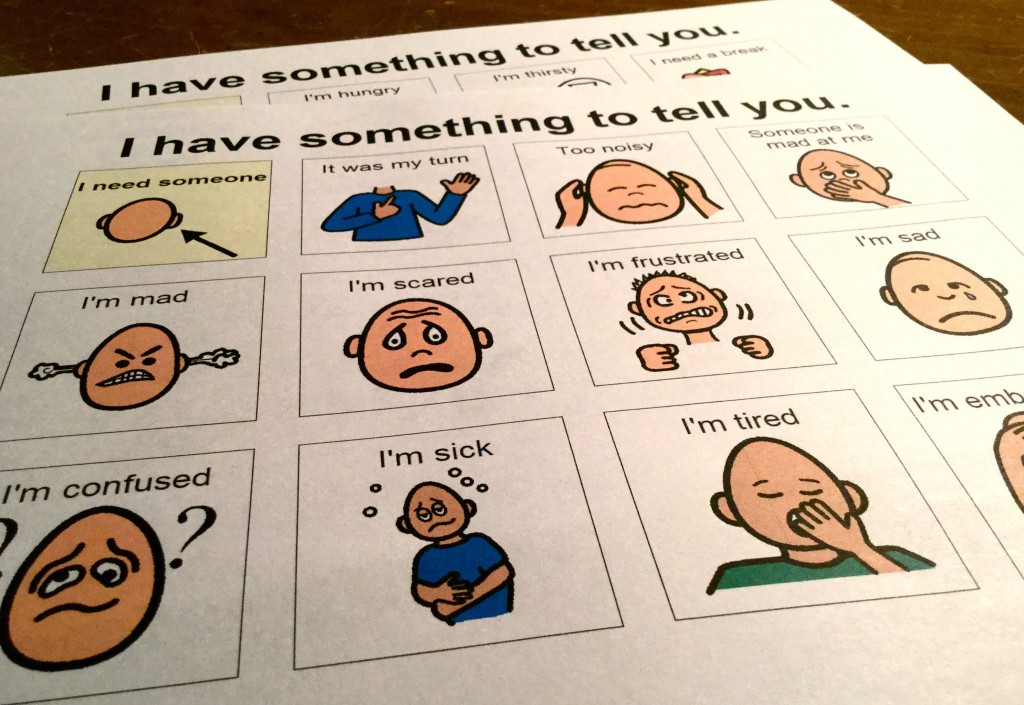

Joan Garbow, a geriatric and disability care manager, suggests finding the right tools to help. “There are alternative communication devices for people who have aphasia (a partial or total loss of the ability to articulate ideas or comprehend spoken or written language). If she can identify words, you can get a communication board with words, or pictures if reading is no longer possible.” Joan recommended iPads with specialized software for language impairments. “Speech and language therapists specialize in this area and should be able to assess which device would be most helpful and provide the best resources,” she said.

Donna Fedus, a gerontologist and the founder of Borrow My Glasses, LLC, suggests switching into detective mode. “I have four suggestions for when verbal channels don’t work so well:

- Look around the environment for clues about what triggered the problem.

- Look for indicators of pain. Is her mom grimacing, rocking, protecting a body part?

- Consider what kind of demeanor and gestures would calm mom down. Simple things like getting her to take an exaggerated deep breath, or reaching out to take her hand and smile warmly to diffuse the anger and frustration.

- Transition her into another activity like walking (to process energy) or art (to calm her and help her express herself).”

Laura Kaplan, licensed clinical social worker and geriatric care manager at Connecticut Eldercare Solutions, LLC, suggests creating a warm and loving presence for Kari’s mom. “Gentle reassuring comments, touch and holding (if this has been part of their past relationship) and movement, like a short walk through the house, looking at pictures and mementos, can help to decrease anxiety.

“Specific and thoughtfully chosen music that her mother may have once enjoyed can also be very useful and soothing,” Laura added. “Prepare an iPod of this music to have on hand. This has been very effective in nursing homes when people are sundowning or upset.

“It is sad and frustrating to feel the loss of verbal communication with a loved one, but these other avenues may help make you feel more connected with her again.”

We surely hope these suggestions prove helpful to Kari and her mother, and that the comfort of knowing she is heard, even when she can’t speak, translates into a sound and restful sleep for Kari’s mom.

Karen Keller Capuciati is the Co-Founder of In Care of Dad.