by Paul Raia, Ph.D.

Some 30 years ago, I was just starting out in the field, working with a neurologist. A 50-year-old woman, with a husband and two teenagers at home, was living in the dementia wing of a nursing home in Massachusetts. Her behavior had the appearance of mid-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD). But, while examining her, the neurologist noticed she had a discernible copper pigment in her eyes and, based on this information, properly diagnosed her with Wilson’s disease.

Wilson’s disease is a genetic problem with metabolizing zinc and copper. Unlike Alzheimer’s, Wilson’s disease is totally treatable when caught early enough. In this particular woman’s case, the disease was too far along and she died within months. However, she had two younger sisters who carried the gene. They began medication that allowed them to avoid the same fate. This simple procedure saved the sisters, her children and the family’s future generations, but she herself paid a high price for the original misdiagnosis. To this day, I always suggest to families, if the diagnosis is unclear, ask their doctor to screen for Wilson’s disease, along with other dementia-causing conditions that may also be treatable.

Dementia is a condition that encompasses memory loss, confusion and disorientation. It’s not a disease itself. It’s like saying someone is blind, in that it is a condition, while glaucoma is the disease that caused the blindness. Alzheimer’s is the disease that most commonly causes dementia — 70% of all dementia cases stem from AD.

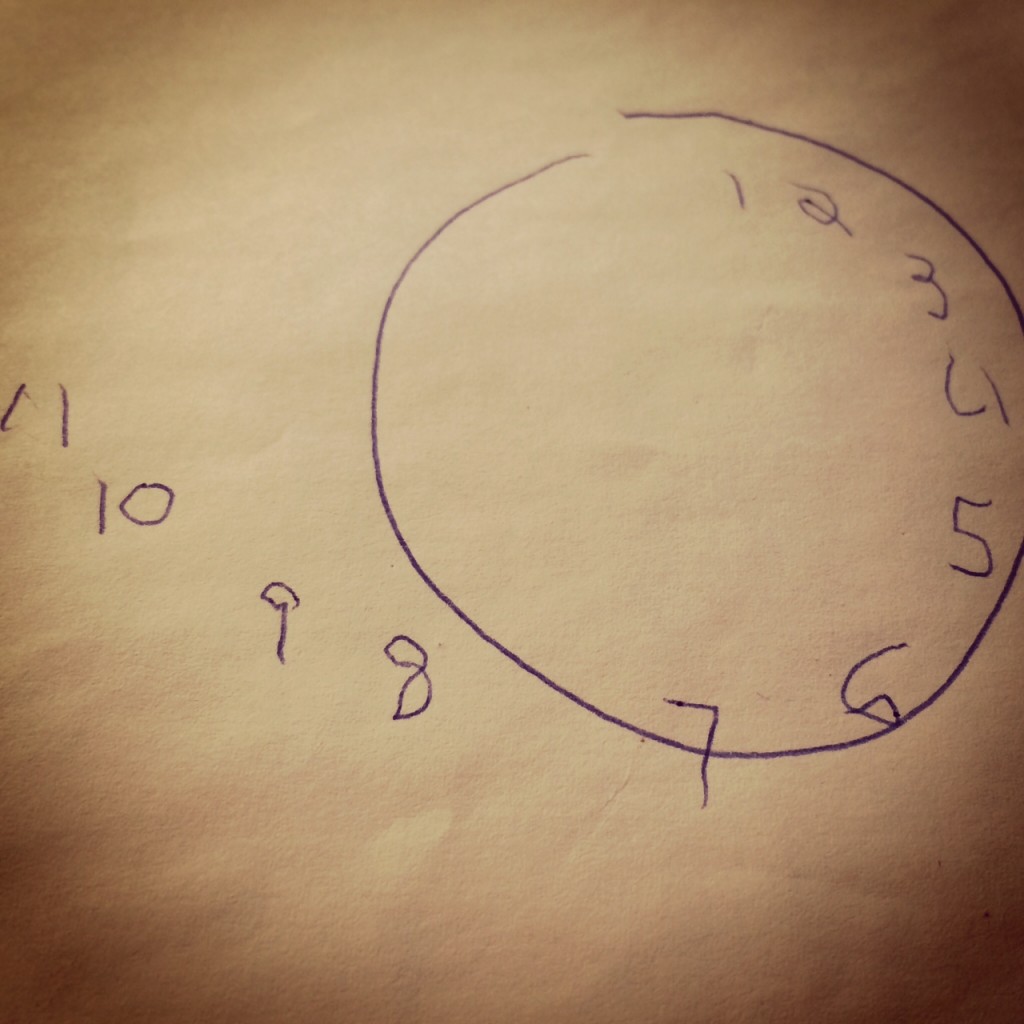

A proper diagnosis process should start with the primary care physician, especially if that doctor knows the patient well and can discern irregular behavior and altered cognitive ability. If you have a friend or loved one suffering with symptoms of dementia, make sure their family has a conversation with a physician to talk about what people are seeing. Make sure the doctor understands the full scope of the behavioral changes. Ask the doctor to take you through the process of ruling out other medical issues that could be responsible for any alarming changes in cognition that might be mistaken for Alzheimer’s. Typically, a diagnostic evaluation would include a lengthy patient history, a full medical and neurological exam to rule out medical causes of the cognitive changes, neuro-psychological testing (a series of paper and pencil tests that may take an hour or more), and, in some cases, various types of brain scans.

There are myriad medical conditions that can mimic dementia, including UTI (urinary tract infection), depression, vitamin B deficiencies, changes in the person’s ability to metabolize nutrients, sleep deprivation, sleep apnea, head injury, uncontrolled diabetes, dehydration, gout, gastrointestinal disorders, Crohn’s disease, undetected food allergies, and diseases borne by insects. Treating these situations may very well alleviate the dementia symptoms. Also, it’s important to be able to distinguish between normal age-related cognitive loss and AD.

Age-related brain loss is normal and can affect linguistics and memory. For example, it could take longer for a person to find the right word, or remember a name. It could also take longer to process and understand verbal information. The person can still do it, but it takes more time. With memory, they may forget a past experience or take longer to remember where they put something, but in each case they can remember with some time.

There are, of course, other related dementia-causing illnesses where the symptoms differ from those we typically see with AD. Worth mentioning is that 41% of those with AD have a mixed diagnosis with other forms of dementing illness. So, in many cases, there are uniquely characteristic symptoms from more than one disease present.

Most of these related disorders are fairly dramatic in their presentation and in most cases should be clear in diagnosis. Like AD, all of these diseases listed below are progressive and without a cure, with the exception of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) which can be reversed with early detection.

Lewy body dementia — LBD is the most common dementia after AD. It often presents with visual hallucinations. Memory is impaired, but typically not as much as with AD. Judgment, on the other hand, is impaired earlier than is typically seen with AD. With Lewy body dementia, disturbed sleep is an issue. Sufferers often don’t get the required four hours of REM sleep, which is when some of the toxins are removed from the brain. Normally our bodies are “paralyzed” when we are dreaming in REM sleep, but people with LBD are able to move and act out their dreams, which disrupts their sleep and can cause them to fall out of bed. Those with Lewy body dementia often have problems with balance (even in the early stages) and characteristically fall backwards. Depression, paranoia and delusions can also present themselves. It’s very unpredictable because the person has periods when they do well, while other times they are worse. There are lots of ups and downs, but the disease is always progressing.

Vascular Dementia — Typically with VD, the person’s memory may be better in the earlier stages (as compared to AD, that is), but they have more problems with judgment, reasoning and decision-making. VD causes problems with language — those with the disease lose syntax and can’t express an idea. Often they articulate a string of words that doesn’t make sense to us, but does to them. They may also be repetitive. Paranoid delusions, depression and hallucinations are all symptomatic of VD. Patients may lose self-awareness. Executive functions, like bill-paying or cooking from a recipe, could be a problem. Other medical issues, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, often compound vascular dementia.

Frontotemporal degeneration — FTD results in the progressive damage to the frontal lobes of the brain affecting behavioral, linguistic and/or motor functions. The patient loses the ability to see the world from another person’s perspective and cannot inhibit basic urges. Judgment, reasoning, and emotional control are affected. Those with FTD could show repetitive or ritualized behavior. Often sufferers have no inner sense of danger, and so they can go off and wander. They may be sexually disinhibited. They experience memory loss but perhaps not as severe if compared in each stage with someone with Alzheimer’s disease. The language component presents as difficulty expressing an idea because they lose grammar, or the meaning of words and symbols, or because it takes much longer to understand and perceive what they want to articulate. If motor function is affected by FTD, the person will have difficulty with movement (coordination difficulty, tremors, stiffness, paralysis), which generally starts on one side of the body before it moves to the other side.

Supranuclear palsy — PSP is a kind of motor disease with dementia along with it. Early stages of the disease include problems with executive functioning (multiple steps or logically sequenced tasks), as well as slight issues with memory, judgment and reasoning (but not as severe as someone with AD). Eye coordination can be a problem — PSP sufferers have difficulty controlling their eyelids, and their eyes tend to fall back in their head. As the disease progresses, they may become spastic or have tremors. Sometimes they have trouble moving their neck or the neck becomes paralyzed. They have problems with speech and moving their tongue.

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus — NPH happens when cerebral fluid doesn’t flow evenly and builds up in one area, creating pressure on that part of the brain. It can be treated if caught early, which re-emphasizes the need for proper diagnoses. Ventricles (cerebral fluid pathways) become enlarged, which also damages the brain. There are significant hallmarks of this disease, as it usually presents with these three symptoms: problems with urination (frequent urge and/or incontinence); problems with memory, reasoning, confusion, and disorientation; and a change in gait (shuffling, tilting and falling forward, having difficulty starting and stopping).

Proper diagnosis helps families to know what to expect down the road, as each of these diseases has a different course. For the most effective management of symptoms, it’s critical to tailor treatments based on what we know about a disease. Furthermore, an accurate diagnosis gives a family valuable information about their genetic risks for that disease.

If you feel that the primary care physician is not well versed in dementia-causing illnesses, or you would simply like a second opinion, ask to be referred to a Behavioral Neurologist or a Geriatric Psychiatrist.

Dr. Paul Raia is Vice President, Professional Clinical Services of the Alzheimer’s Association, MA/NH chapter, and is also the chapter’s Director of Patient Care and Family Support.