by Kim Keller

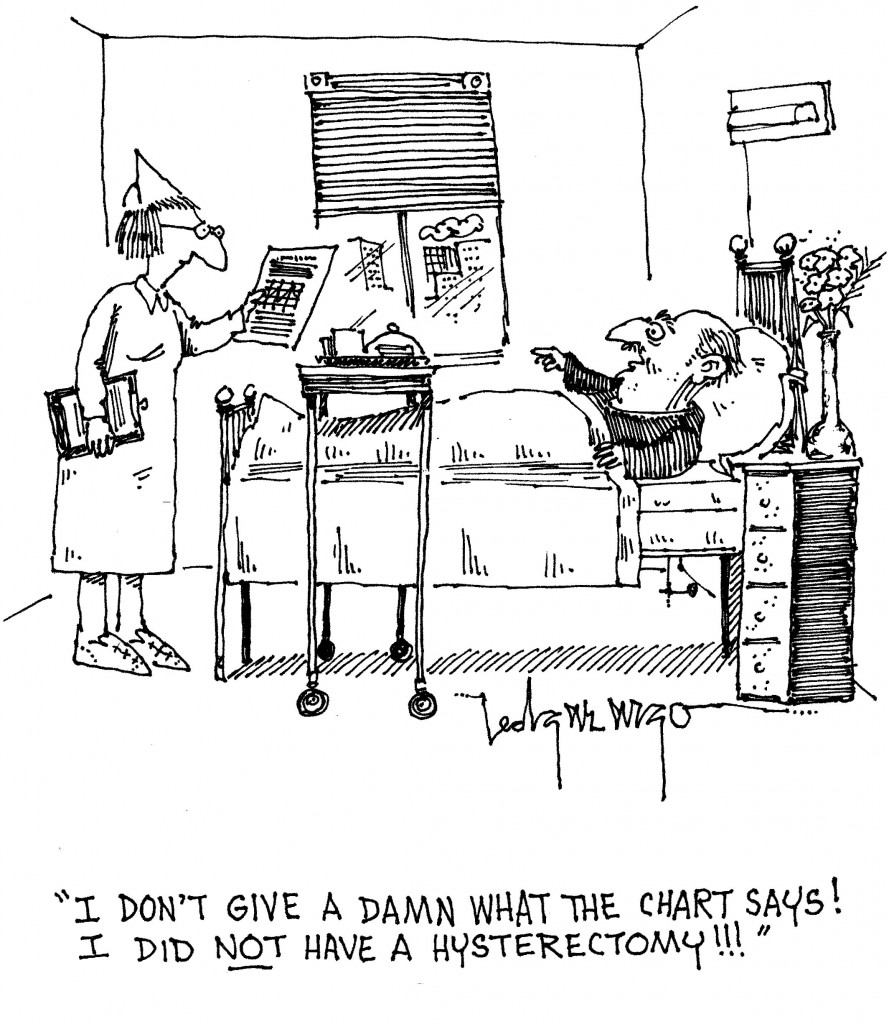

Did you ever wonder if all of the tests, treatments and medications that doctors order are really necessary? Karen and I started wondering about this during our dad’s illness, and we became even more convinced it was true when our mom had a stroke a few years ago.

Naturally my curiosity was piqued when I noticed the cover story in a Newsweek from a few months ago (August 14, 2011), entitled “One Word That Will Save Your Life: No!” Research by the author, Sharon Begley, brings to light the fact that many low-risk patients with light symptoms at best, some with no symptoms at all, suffer more harm than good from various types of tests, procedures and medications.

“There are many areas of medicine where not testing, not imaging, and not treating actually result in better health outcomes,” says Dr. Rita Redberg, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and the editor of the American Medical Associations’s Archives of Internal Medicine. “Less is more,” she explains.

How can that be? I’ve certainly grown up to believe that tests are good, because they can detect a potentially serious problem early enough to effectively treat it, like mammograms, for instance And, to extend that idea, treatments and medications can and do miraculously heal at times. Regardless, Begley points out that there are significant dangers, too. For example, many tests can produce false-positive results, or as the Newsweek article points, sometimes technology gets ahead of human diagnostic capability.

“Our imaging and diagnostic tests are so good, we can see things we couldn’t see before,” says cardiologist Michael Lauer of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. “But our ability to understand what we’re seeing and to know if we should intervene hasn’t kept up.” According to Lauer, doctors can be “fooled” by what they see. “All you’ve done is misclassify someone with no disease as having a disease.”

The potential harm of intervention — exposure to radiation, complications stemming from invasive treatments, side effects from medications, unnecessary anxiety — should not be underestimated. There are a variety of potentially misused tests, treatments and medications discussed in this article, such as PSA blood tests for prostate cancer, annual EKGs, cardio-stress tests, antibiotics for sinus infections.

One of the most surprising parts of the article was the questioning of the surgical procedure known as stenting of blocked blood vessels. Begley reports on studies that were conducted with heart patients who were stable at the time and experiencing only mild chest pains. It seems logical that a stent (a metal coil that opens blood vessels) would prevent heart attacks and strokes, but such is not the case. “That’s because when you disrupt these blockages through surgery, you spray a whole lot of debris down into the tiny blood vessels, which can trigger a heart attack or stroke,” explains Dr. Nortin Hadler, a professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina and the author of Rethinking Age. “Every study found that the surgical procedures didn’t improve survival rates or quality of life more than non-invasive treatments including drugs (beta blockers, cholesterol-lowering statins, and aspiring), exercise, and a healthy diet.”

Although the article doesn’t directly go into this, it’s certainly worth mentioning that Medicare pays doctors by volume of treatments, which tends to keep this cycle pumping. I would also imagine that the fear of potential lawsuits inclines many physicians toward medical intervention. And let’s not leave out the patients’ complicity in this cycle. Many of us — patients just like you and I — want action. We have seen and read and heard about so many miracles in modern medicine that it’s easy to believe in the curative powers of tests, treatments and medications.

So where does that leave us? We need to be active in making our health care choices. We need to talk with our doctors (or our loved one’s doctors) about whether they have considered our family history, all of the symptoms (or lack thereof), and ask point-blank what is to be gained by going down a certain path. What are the potential risks? Is wait-and-see an option? Could we try a change in diet and exercise first? Is there a benefit to medication? What are the side effects?

Open and thorough communication between patient and doctor is the key.

I hope everyone will take a few minutes to read Begley’s article because it’s truly important and then I hope you’ll pass it along.

Kim Keller is the co-founder of In Care of Dad. She lives and works in New York City.